Located in the peaceful village of Jukkasjarvi in Swedish Lapland, the iconic Icehotel provides a unique stay for travellers. Every winter, the Icehotel opens its frozen doors to showcase brand new designs for its ice suites. From sharks and jellyfish, VW camper vans and Victorian libraries to the ever-popular ICEBAR and charming Ice church, guests are treated to a true winter wonderland experience as they sleep in a hotel made of ice. We take a look back at some of our favourite Art Suites from the original ice hotel over three decades.

ICEHOTEL #32

The ice suites of Winter 2021/22 saw the return of artists and designers from around the world following the purely domestic line-up due to the pandemic of the previous year. This collection of sculpted Art Suites include a hexagonal Art Deco interior in the ‘Great Gatsby’ and a band of monkeys and a prehistoric dinosaur crashing the party in the ‘Room Service’. Perhaps the most striking suite is an imagining of Dickens’ London in pure ice. ‘Dickensian Street’ is the latest creation designed by British father and daughter duo Jonathan and Marnie Green.

- Dickensian Street by Jonathan and Marnie Green

- A Midsummer Nights Dream by Carl Philip Bernadotte and Oscar Kylberg

- Great Gatsby by Tomasz Czajkowski and Tomasz Jastrzebski

- Blue Tundra by Elisabeth Kristensen

- To Bed with the Chickens by van de Wetering and Stijger

- Room Service by Ulrika Tallving and Tjasa Gusfors

ICEHOTEL #30

Winter 2019/20 saw the 30th anniversary of the Icehotel. This incarnation of the hotel marked three decades since Icehotel founder Yngve Bergqvist started a journey that would lead to the world’s first hotel made entirely out of snow and ice and during that time over one million guests from all continents of the world have visited.

This build under the guidance of the hotel’s new Creative Director, Luca Roncoroni, featured 15 art suites designed by 33 artists from 16 different countries making it the largest group ever. From checking a frozen West End theatre production to a subterranean ice room with giant ice ants, a frozen feline lair to the Greek island of Santorini depicted in ice, 2019/20 offered an incredible range of rooms.

- A Night at the Theatre by Jonathan Paul and Marnie Green

- White Santorini by Hamee Han and Jaeyual Lee

- Subterranean by Daniel Rosenbaum and Jörgen Westin

- Kaleidoscope by Natsuki and Shingo Saito

- Golden Ice by Nicolas Triboulot and Jean-Marie Guitera

ICEHOTEL #29

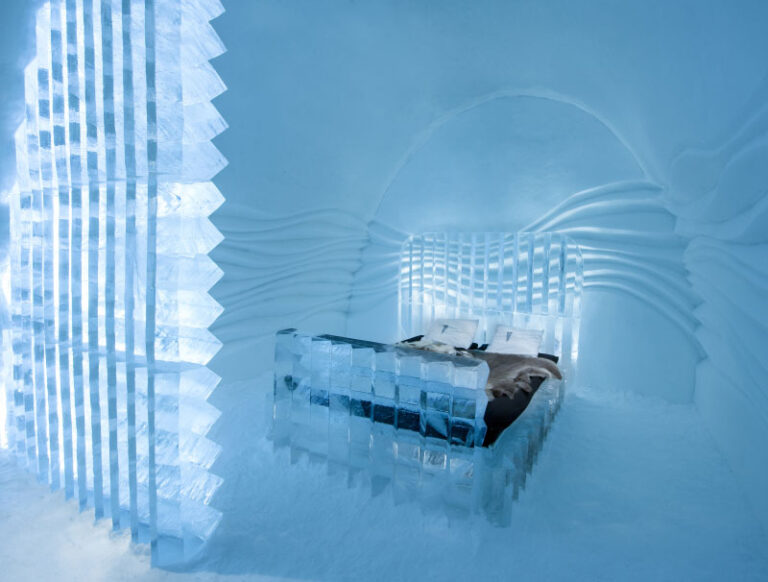

December 2018 witnessed the opening of the 29th incarnation of the iconic Icehotel in Swedish Lapland. The art suites created an experience for those curious at heart as the reoccurring inspiration for these artists was nature. Surrounded by raw beauty, guests could walk through a spectacular ice forest or to incredible skies. You could even dive deep and marvel at an underwater world filled with corals and fish.

“The suite is inspired by the climate changes and the over-fishing that affects our oceans. I also thought the idea of using frozen water from a river in northern Sweden to create an ocean with shells, fish, and corals is exciting. – Jonathan Paul Green

- The Living Ocean Suite by Jonathan Paul and Marnie Green

- Haven by Jonas Johansson, Jordia Claramunt & Lu

- Spruce Woods by Christopher Pancoe & Jennie O’Keefe

- Lollipop by Mathieu Brison & Luc Voisin

- Differential Expansion by Antonio & Juan Carlos Camara

ICEHOTEL #28

The 2017/18 season brought many surprises with a few designs taking inspiration from classic films. You could have been snuggled in the arms of a gigantic King Kong or drifting into dreamland under the watchful eye of a snow queen. With suites inspired by giant snails, desert wilderness, a frozen jungle and icy cloudscapes, nature was once again a reoccurring theme.

Icehotel #28 saw the introduction of the Chef’s Table dining experience at the ICEHOTEL restaurant. Featuring a 12-course tasting menu by an award-winning head chef.

- King Kong by Lkhagvadorj Dorjsuren

- Queen of the North by Emilie Steele & Sebastian Dell’Uva

- Daily Travelers” by Alem Teklu & Anne Karin Krogevoll

- Cumulus by Annakatrin Kraus & Hans Aescht

- Monstera by Nina Kauppi & Johan Kauppi

- Follow the White Rabbit by Anna Sofia Mååg & Niklas Byman

- A Rich Seam by Howard & Hugh Miller

- Hang in There by Marjolein Vonk & Maurizio Perron

- LIVOQ by Fabien Champeval & Friederike Schroth

- Space Room by Adrian Bois & Pablo Lopez

- Ground Rules by Carl Wellander & Ulrika Tallving

- Radiance by Natsuki Saito & Shingo Saito

- The White Desert by Timsam Harding & Fabián Jacquet Casado

ICEHOTEL #27 and 365

During this season, Icehotel 365 opened up its doors for the first time. Bringing a permanent ice experience, 365 has nine deluxe suites, each with their warm bathroom and sauna, as well as eleven art suites.

In 2016/17, the hotel offered more creativity than ever in its history. It showcased incredible themes such as the Japanese art of flower arranging and the passion of sleeping inside a dream. It also featured a house of cards made from ice and snow, a palace inspired by Casablanca, and a cherry tree made to last the winter. These are a few of the ingenious sculptures that defied the elements at the 27th ICEHOTEL.

ICEHOTEL #26

Imagine a three-meter African elephant carved out of snow. What about a 1970s inspired Love Capsule? Even an imperial Russian-inspired theatre set, Labyrinth Saga. Those were some of the creations created for the 2015/16 edition of the ICEHOTEL. This year also introduced extra exciting activities:

- Swedish sauna ritual experience including ice plunge and thermal starlit bath

- Northern lights wake-up calls straight to guests’ smartphone

- Arctic wilderness survival beginners’ course – this includes building a shelter and making fire

- Elephant in the Room by AnnaSofia Mååg

- Cesare’s Wake by Petros Dermatas and Ellie Souti

- Eye Suite by Nicolas Triboulot and Cédric Alizard

- The Flying Buttress by AnnaKatrin Kraus and Hans Aescht

- Show Me What You Got by Tjåsa Gusfors and David Andrén

The Best of the Rest

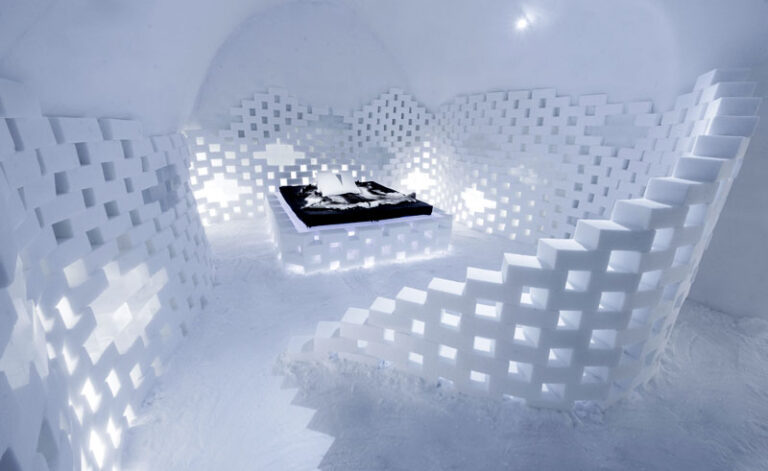

Since opening, the hotel has featured over 400 different designs! We’ve singled a few of our favourites that have captured our imagination over the years.

During the 150th anniversary year of the London Underground, British film director Marcus Dillistone built his “Mind the Gap” Art Suite depicting a Tube platform in ice. Another one of our favourites was the “Abject Beauty” suite. The creators have worked with complex sculptures to create a sense of the unpredictable. With their abstract world, they hope to change people’s ideas of what they consider ‘beautiful’.

“We wanted to create a world within the world. A world full of patterns and shapes that fill the room and create a captivating scene.”

- The Mushroom Suite by Viktor Tsarski and Liliya Pobornikova (ICEHOTEL #19)

- Fridge Suite by Macus Dilliston (ICEHOTEL #21)

- Blue Marine by Andrew Winch & William Blomstrand (ICEHOTEL #23)

- Mind the gap by Marcus Dillistone & Magdalena Åkerströ (ICEHOTEL #24)

- Abject Beauty by Lotta Lampa & Julia Gamborg Nielsen, Sweden (ICEHOTEL #25)

Visiting the Icehotel

We offer an extensive collection of Icehotel holidays, including irresistible multi-centre combinations. Between December and early April you can visit the seasonal winter hotel or choose to visit at any time of year staying in Icehotel365.

Instagram

Instagram

Facebook

Facebook

YouTube

YouTube