As volcanic eruptions continue on Iceland’s Reykjanes peninsula, travel writer William Gray talks to the experts to find out what’s really happening…

Fire and brimstone. Fountains of molten rock. Dramatic footage of roads and, tragically, even houses being consumed by lava. Like me, I expect you’ve been engrossed by footage of the volcanic eruptions in Iceland. There are few things in nature more mesmerising than smouldering rivers of lava snaking through a charred landscape. But equally there is something humbling about witnessing the unstoppable power of this primeval force.

Not surprisingly, social media is getting carried away – so much so, in fact, that some sources have fanned the flames to portray Iceland as unsafe to visit: a ‘no-go area’.

The reality couldn’t be further from the truth. Iceland is open for business as usual.

I was there in September 2023, hiking to one of the recent eruption sites. It’s become a tourist attraction, complete with car park and walking trails. That was in a remote, uninhabited part of Reykjanes – the rugged boot-shaped peninsula in southwest Iceland that’s home to the international airport at Keflavík and the Blue Lagoon, and adjacent to the capital, Reykjavík. When it was active, the eruption attracted crowds of people – locals and tourists eager to witness what, to many, is a once-in-a-lifetime spectacle.

But that’s the thing isn’t it. These eruptions are not ‘once-in-a-lifetime’. From March 2021 to May 2024, there were no fewer than eight volcanic eruptions on the Reykjanes peninsula, with a ninth starting on 24 August 2024 and lasting 14 days. Experts are predicting that there could be many more over the coming years.

Ari Trausti Guðmundsson, one of Iceland’s leading geologists, tells me “The previous period of unrest lasted for about three centuries. In each century there were about 30 years when we had eruptions.”

Could we have predicted this was going to happen?

“We have seen back in time that there have been cycles of volcanic activity with the peaks occurring every 750-800 years,” Guðmundsson explains. “The last bout of eruptions came to an end in 1240, so if you add 750-800 years to that, where are you…?”

So, not only does the Reykjanes peninsula appear to be getting lively right on schedule, but it might well be the start of a period of volcanic activity that lasts decades, if not centuries. I’m keen to find out what this potentially means for both Icelanders and tourists – but first I wanted to delve into the geology of Iceland, to understand why and where this is happening.

If the rocks could talk

Iceland’s geological history is a fiery saga. The island was born from volcanic action, emerging above the waves of the North Atlantic some 18-20 million years ago. Straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge – a 16,000km-long chain of submerged mountains and volcanoes – it truly is a geological wonderland. Iceland’s unique position at the boundary between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates means there are places where you can actually walk, or even snorkel, between the plates that support two continents.

But contrary to what scaremongers are saying, Iceland is not one giant, angry volcano that’s poked its head above the Atlantic. You only have to glance at a geological map of the country to see that its volcanic systems are mainly restrained to a corridor running across the country from the southwest to the northeast – with most of the volcanoes and hottest geothermal areas located in the remote interior, far from towns and villages.

“Volcanic activity in Iceland is not a random thing,” says Guðmundsson. “The earth cannot split open anywhere in Iceland and spout lava.”

And that applies to the Reykjanes peninsula too, he tells me. “Within this active zone, volcanic fissures do not appear at random, but are confined within elongated areas, bounded by fissures, faults and volcanic formations.”

Look at an aerial photograph of one of the recent Reykjanes eruptions and Guðmundsson’s words literally leap out in front of you: the lava is erupting along narrow fissures. They’re usually short – perhaps two to four kilometres in length – and they follow the fault lines that Guðmundsson is describing. “Lava will always find the easiest way to reach the surface,” he explains.

That leads to an obvious question: are there fault lines that could lead to volcanic eruptions in Reykjavík or at Keflavík airport? “Absolutely not,” he replies. “That’s impossible. The rift axis [of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge] enters the southwest of the Reykjanes peninsula and then it’s bent inwards and heads east.”

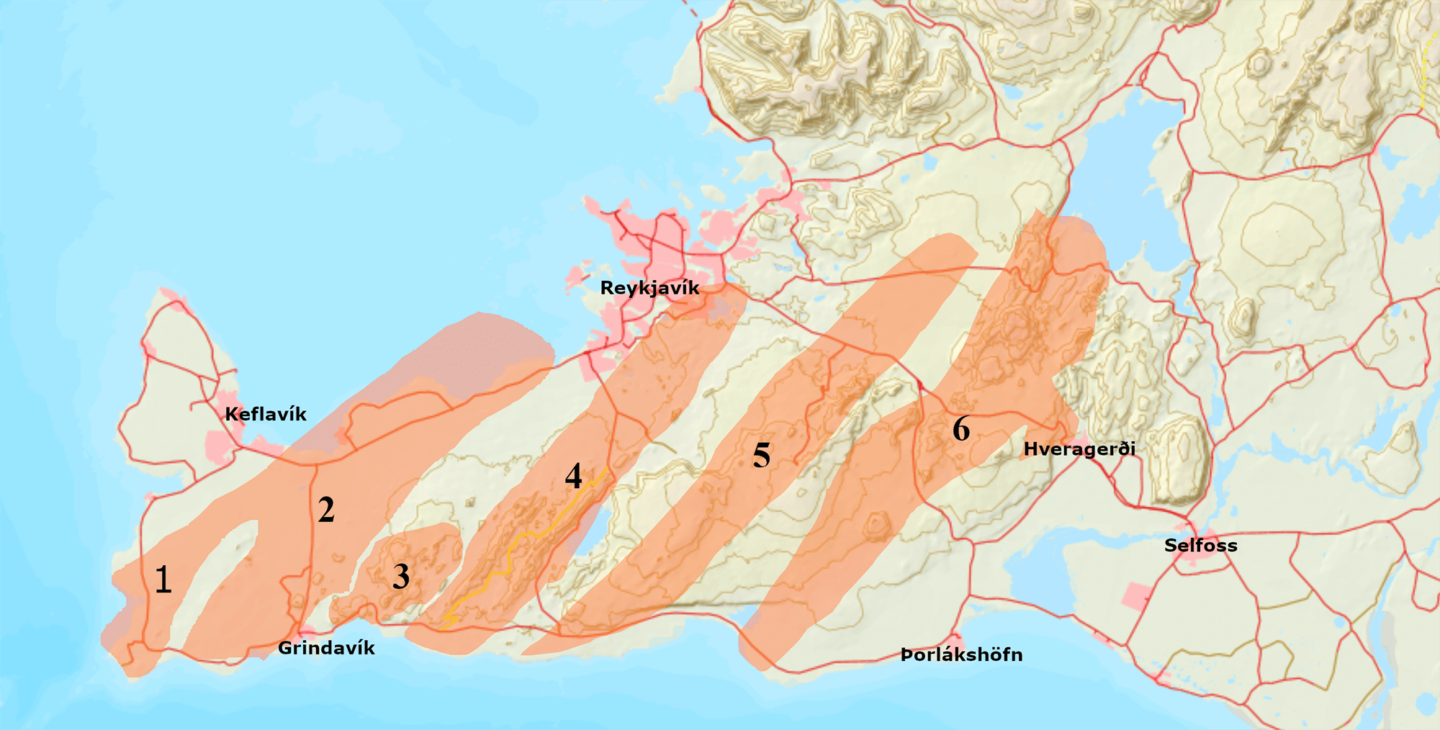

That’s significant because both Reykjavík and Keflavík airport are on or near the northern edge of the peninsula. Geologists like Guðmundsson also know that there are six volcanic systems on the Reykjanes peninsula – each one a narrow band orientated in a southwest-northeast direction. Imagine the Mid-Atlantic rift is a deep scar running through the peninsula and the six volcanic systems resemble stitches lying across it.

“The extremities of each volcanic system are not active,” says Guðmundsson, which further removes the threat of a volcanic eruption near Reykjavík or the airport.

But what of Grindavík on the south coast of the Reykjanes peninsula? When a fissure opened in January 2024, lava flowed into the northern outskirts of the town and destroyed three houses. There was no danger to life. The population of around 3,800 people had been evacuated long before the eruption – a sign of just how effective the Icelandic authorities are at monitoring seismic activity. Our hearts go out to the displaced inhabitants of Grindavík, but the Icelandic government has moved fast to rehouse them in other parts of the country. It’s all part of a well-rehearsed machine that’s designed to deal with the reality of living in the Land of Fire & Ice.

Living with volcanoes

“In Iceland we learn from birth to respect the nature,” Friðrik Einarsson, owner of the Northern Light Inn, tells me. “It is in our DNA to adapt to the challenges Mother Nature brings us at any given time. While eruptions are breathtaking to experience, we understand – and respect – their power.”

Tucked into an ancient, surreal lavascape near the Blue Lagoon and Svartsengi power station, the Northern Light Inn is a superb base for experiencing the volcanic scenery of the Reykjanes peninsula.

“During the recent volcanic events there has not been any immediate danger to our hotel guests, staff or facilities,” explains Einarsson.

Even if the hotel has to be closed occasionally as a precaution, the infrastructure in the area is remarkably well-maintained. You might think, for example, that lava flowing across a road would block access indefinitely. But that’s not the case at all.

Ragnar Th. Sigurðsson is one of Iceland’s most renowned photographers – his images and footage of Iceland’s volcanoes have gained worldwide recognition. Sigurðsson also works for a local construction company.

“It was still glowing when we started rebuilding the road,” he tells me when I ask him about his striking images of lava engulfing a road on the Reykjanes peninsula in February 2024. “The top of the lava flow starts to cool down immediately, so you can build a new road on it the day after by putting some gravel and stuff over the top. You can drive or walk over it, even though it’s still warm when you touch it. There’s no danger. They’ve also laid new pipes over the lava flow to carry hot water.”

Sigurðsson stresses that these roads are not necessarily open to the public, but they do provide access for emergency vehicles and act as evacuation routes if needed.

Electricity supplies also have to be protected, with pylons surrounded by a circular wall of rock and gravel 6-8m high and 10m wide.

“You cannot stop a lava flow,” explains Sigurðsson. “It’s heavy, and the force is so great. But you can change its direction. If a lava flow hits one of the barriers we’ve built, it can flow away from the town, away from the Blue Lagoon, away from the power plant.”

That’s Icelanders for you. A lava flow isn’t going to defeat them.

But what’s it like to stand there and watch a volcanic eruption taking place in front of you?

“Let me put it this way,” says Sigurðsson “I’ve been photographing volcanoes since 1975. I’ve photographed every volcano and every eruption in Iceland for nearly 50 years. And it always awes me. I’m just standing in front of it and saying “Wow!””

Do you ever feel unsafe or threatened by it?

“No. I don’t go towards the volcano before it erupts. I wait to see where it is and how it behaves. I wait until we can access it very safely. No one is allowed to get closer than is safe.”

Witnessing an eruption

Safe eruptions. Tourist-friendly eruptions. These are terms you hear a lot in Iceland, and I’m keen to find out more. Clive Stacey is the Founder and Managing Director of Discover the World – the world’s leading Iceland specialist with 40 years of experience.

“When it’s possible to witness a ‘tourist eruption’, we suggest you don’t run in the opposite direction,” he tells me. “It’s one of life’s most amazing experiences!”

Like Sigurðsson, Stacey has been in awe of Iceland’s volcanoes for some 50 years. He recalls North Iceland’s Krafla eruption of 1984: “We were the only people around. Darkness had fallen and we stood on a hill at the edge of the lava flow and watched, spellbound, as the crater spewed lava into a ‘molten orange sea’. A breeze whipped the lava into small tornadoes, which floated across the scene like ghosts. Then the clouds parted, revealing a spectacular display of the northern lights.”

So, what advice does he have for anyone keen to follow in his footsteps?

“The main thing to remember about viewing a volcanic eruption is to carefully follow advice and preferably do it with an expert guide. That way you will not only be as safe as possible, but you will also learn some fascinating information about what you are viewing. Even though some volcanic activity can appear relatively harmless, there can be dangers when you get too close, such as breathing in fumes or walking on ground which is unsafe. Although nobody has been killed directly by volcanic eruptions in Iceland for over 200 years, it’s important not to take liberties!”

Sign up to Discover the World’s Volcano Hotline and you will be alerted when there’s a tourist-friendly eruption that’s safe – and appropriate – to visit. We also offer Volcano Disruption Protection on holidays to Iceland: Should the unexpected occur its team of dedicated Travel Specialists are on call 24/7 to make any necessary alternative plans at no cost to you. It’s an unmatched level of support that adds even more peace-of-mind to its already robust 100% Guarantee.

Still unsure about whether Iceland is safe to visit?

Dr Matthew Roberts, Managing Director of the Icelandic Met Office, offers these words of reassurance: “The ongoing volcanic unrest will no doubt continue, but the eruptions are small in intensity, they’re confined to a small part of the Reykjanes peninsula, and the hazards do not project to great distances. There’s no emission of volcanic ash, no lightning strikes, nothing that you would expect to see from a much larger volcanic eruption from a typical peak-shaped volcano. So, everyone is encouraged to visit, airports are open, travel is open and business goes on as normal.”

Get in touch

If you’d like to plan a visit to the Iceland, drop our Travel Specialists a line on 01737 214 250 or send an enquiry.

Images by Ragnar TH Sigurdsson, William Gray, Northern Light Inn

Graphic by National Land Survey of Iceland, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

Instagram

Instagram

Facebook

Facebook

YouTube

YouTube